How Do We Get Infill Right? Lessons from Recent Zoning Reform Examples

- Jul 18, 2025

- 5 min read

We’ve all seen the same housing story play out: A city takes bold action, upzoning to spark a wave of new infill housing. Almost immediately, NIMBY opposition erupts, taking the form of heated public meetings, petitions, and a flood of emails. In response, council retreats, scaling back the new permissions, and the housing crisis persists.

In this article, we explore how Edmonton and Ottawa have approached infill, offering practical examples of what works, what sparks friction, and how smarter zoning, design, and engagement can lead to better outcomes for communities.

Edmonton Brings in 8-Unit Allowances

Edmonton’s recent experience is a case in point. The city’s move to allow eight units per lot in 2023 led to a surge in new infill, with 71% of new mid-block building permits issued for 8-unit buildings. While this growth addressed housing supply, it also raised a host of concerns. Compounding the issues, some eight-unit buildings designed for corners were awkwardly placed mid-block, disrupting neighbourhood flow. As frustrations grew, so did a political firestorm. Just last week, the city council found itself split by the slimmest of margins—six councillors voted to maintain the eight-unit cap, while five pushed to reduce the cap to six units on mid-block lots. This story underscores the contentious nature of densification, even in cities with a reputation for progressive planning.

At the same time, council approved additional amendments to the zoning bylaw aimed at improving neighbourhood compatibility, considerations that weren’t included in the original upzoning. These changes include requirements for street-facing façade glazing, restrictions on the number of side doors facing neighbouring homes, and stricter building size limits on some lots. While these changes may seem modest, developers warn that such restrictions can be deal breakers, particularly reducing building envelops on smaller or irregular lots, potentially pushing developers back toward less sustainable suburban developments. This is a cautionary tale highlighting the need to balance viable business models with contextually-appropriate development, in order to achieve successful neighbourhood intensification.

Ottawa Tests How Zoning Can Shape Front Façades of Small Apartments

Ottawa offers another example showing how zoning reform can advance infill housing. In 2020, the city set out to revise its zoning to allow small apartment buildings in urban neighbourhoods that might otherwise see overcrowded or unsuitable housing types. Rather than rushing into complex zoning changes, city planners worked with our team to stress-test the proposed zoning rules first. This proactive approach provided a clear forecast of how the market would respond, pinpointing where infill was most likely to occur and what building sizes and unit counts residents could realistically expect. This ensured that both planners and neighbours had a transparent and accurate picture of the future development before any changes were made.

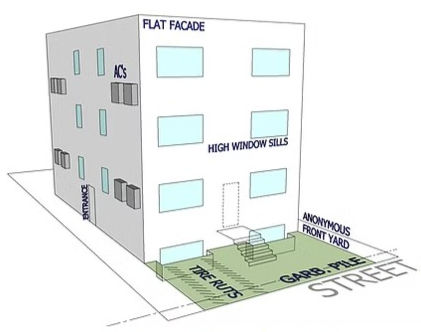

Going further, our team modelled potential building features and worse-case outcomes of designs, that would meet the proposed future zoning, but that would not be appropriate in the streetscape.

That visual revealed some potentially jarring building details, leading our team to recommend adding some form-based zoning clauses to the new rules, as diagramed below. This approach would ensure that street-facing facades would not only be functional but would also enhance the character of neighbourhoods. The resulting industry response has been a steady stream of new multi-unit infill buildings that animate the street and are a good fit. Now, as the city prepares its next zoning draft for 2026, it is building on this success by expanding these principles even further.

The Psychology of Casual Encounters

Charles Montgomery’s Happy City (2013) makes a compelling case: the way we design our cities has a profound impact on our happiness, health, and sense of community. His research reveals that streetscapes are more than just visual backdrops—they are places for everyday human connection. He compares the experience of living in a 29-story tower in Vancouver’s Yale district, with living in a townhouse.

“Within weeks his social landscape was transformed. He got to know all his new neighbors… The front doors of the town houses all led to semiprivate porches overlooking the podium garden. They provided regular opportunities for brief, easy contact. These porches were a soft zone, where you could hang out or retreat as you wished.”

- Charles Montgomery, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (p.133)

These features like front porches where neighbours can chat, benches where someone can pause for a conversation, or sidewalks that encourage people to linger all help turn routine activities, from walking the dog to picking up groceries, into chances for interaction.

Within our Urban Planning industry, there isn't a lot of awareness of the importance of social dynamics. In contrast, in Denmark, every planning application must provide a rationale for the proposed development in terms of its contribution to the social dynamic of the surrounding urban spaces and places.

Given this research, we were curious to learn if Canadian Urban Planners and urban enthusiasts could recognize the features that support social interaction in front of low-rise infill housing. We surveyed over 400 planners and urban enthusiasts to find out. Participants evaluated a range of images showing different levels of socially-dynamic features on infill examples. While the survey wasn't scientific, it showed that most people were able to recognize that front porches, large windows, balconies, and semi-private spaces at the front of buildings are key to fostering inviting, socially-active environments.

What Makes a Socially-Dynamic Home Façade?

So how do we move beyond merely hoping for better social dynamics, to ensuring that our intensifying neighbourhoods are becoming better places for community life? Many municipalities have relied on design guidelines or review committees, but these add uncertainty, and slow or even scare development away.

The answer lies in zoning.

We’ve developed form-based zoning templates with language that would require animated, socially-dynamic facades, because the evidence is clear: people are happier and feel safer in neighbourhoods where buildings invite interaction and life spills onto the street. It’s time to make these people-friendly features a rule, not just a suggestion.

Writing Social Design Features into the Rules

The experiences of Edmonton and Ottawa reveal important lessons: successful infill development requires more than just increasing density. The answer isn’t simply “more units.” The devil is in the design details: from the quality of facades and streetscapes to the way new buildings invite social connection and fit within the community fabric, every decision matters.

Settling for the bare minimum by simply increasing unit counts is no longer enough. We need to insist on creating neighbourhoods that residents feel add real value to their lives. This requires bold leadership committed to prioritizing social dynamics. Zoning is the right tool for the job—to foster streets where people want to walk, linger, and socialize instead of just driving by. It is critical that we get this right—and get it done quickly—while keeping housing development on track and avoiding added uncertainty for builders. Building neighbourhoods that inspire pride and connection must be the standard, not an afterthought.

Bring animated, people-focused facades to your city!

Want to learn more about integrating socially-animated facades into your zoning? Get in touch with our team today to set up a free discovery call.

Comments